The Big Read – Dongfeng (1/6) – The longest conception in automotive history

The Second Automobile Works (SAW) started limited military production in the late 1960s and civilian production in the mid-1970s. This is contrary to China’s major state-owned car manufacturers, that mostly have their origins in the early 1950s. Despite its late arrival on the scene, SAW’s establishment was already instructed by Mao Zedong himself in late 1952, only months after the all clear on the country’s first car factory, First Automobile Works (FAW). With almost two decades separating plan and implementation, SAW has one of the longest birth periods in automotive history.

The first attempt

FAW was established in Changchun in the northern province of Jilin. At the time it was one of the few somewhat industrialised areas of China and a relatively prosperous region, due to its resource industry (mostly coal mining). But the north-east of China was also a strategically vulnerable area, that had seen many invasions and foreign occupiers through the years. For security reasons the Chinese government planned to set up back-up manufacturing capacity in places not so prone to enemy attacks. The committee overseeing the SAW plan based itself in Wuhan in central China.

The committee chose a site in the Wuchang district, which had great economic advantageous. The region already had some industrial activities, concentrated in and around Wuhan. It had reasonably well connections to rest of the country, while still being relatively secluded in the mountainous interior. The Machinery Ministry however rejected the plan for strategic reasons. The industrial area of Wuhan was located on a plain area with several factories in close vicinity. It could be easily attacked from the air, once war broke out.

It wasn’t the end of the first attempt though. A new location was proposed in 1955, Chengdu in Sichuan province, which is much further inland. An empty field on the eastern outskirts of the city was chosen and construction of a large dormitory started the same year. It quickly fell behind schedule as the construction sector was overwhelmed by large number of infrastructural projects around the country. There was also disagreement between various parties over the proposed size of SAW, so in 1956 the projects was put on hold temporarily.

Strike two

Two years later, Chairman Mao sent soldiers returning from the Korean war over to the Jiangnan region (the area around Shanghai end the Yangtze river delta) to prepare for the construction of SAW. This time it was China’s prime minister (Li Fuchun), who derailed the plans. He proposed the other end of the Yangtze river, in the Hunan mountains, as a favorable site. The Machinery Ministry agreed with the prime-minister and did a preliminary site selection in Hunan province. In April 1960 all parties involved decided on a location, but again the it all fell apart before the first spade was in the ground. This time it was economic trouble and lack of funds, which led to the plans being shelved again.

Not there yet

In the early 1960s China friendly relations with the Russians quickly deteriorated, while relations with the Americans remained strained and China was continuously challenged by neighbouring countries like Vietnam. The security situation had become more demanding, so Chairman Mao proposed the Second Automobile Works for the third time in 1964. This time he added it should be located near a major railway.

The Machinery Ministry carried out another round of possible sites evaluations. It inspected sites in Sichuan, Guizhou and Hunan province. It selected a piece of land between the Chenxi, Luxi and Songxi villages in Hunan, along the proposed Sichuan-Han railway. To emphasise this time they meant business, over 30 people were recruited from Changchun Automobile Research Institute, the Central South Industrial and Architectural Design Institute of the Ministry of Construction and Engineering and the Central China Survey Brigade to start the preliminary work.

After thorough inspection a definitive plan was sent to the central government in October 1964. And again the project was derailed, this time literally. The government had just changed the planned route for the Sichuan-Han railway. No longer it would pass through Hunan, but it would go through Hubei province instead. So we’re basically back at square one, because the team returned to Wuhan to make new plans… again.

Another round of site selection and inspections followed and this time the choice landed on Shiyan, a remote, rural village populated by a few hundred people, deep in the mountains of Hubei. At this time the government had appointed a growing number of specialists from all over the country to the project, but mainly coming from FAW. There was a car to be developed. In October of 1966 the final decision followed, Shiyan was going the to be place and construction of a factory began immediately.

Only to stop again almost right away.

Three times is still a charm

You might remember 1966 was also the year of the Cultural Revolution. This was Mao’s campaign to rid the country of all revisionist thinking and apply the communist society he described in his Little Red Book. The ten year long campaign was a disaster of civil unrest, economic hardship and bloody political assassinations. Also question were raised about the viability of SAW in Shiyan. The Machinery Ministry reviewed the whole process again and decided they were right after all. So in 1969 the second automobile factory finally started construction. This time for real. Second Automobile Works is established as a company in September of that year.

Despite, or maybe thanks to the long birth process, SAW is probably the only car manufacturer that produced cars before it even existed. SAW held a low key groundbreaking ceremony in 1967, while construction of the factory would only start two years later. In the meantime the growing number of engineers assigned to the project, coming from FAW, Beijing Automobile Works and Nanjing Automobile, built a small wooden shed on the property that served as workshop. The group produced a number of 2 and 2,5 ton trucks in this shed, early prototypes mostly. But it also hand-built the first series of trucks to be sold there, while the factory was still under construction.

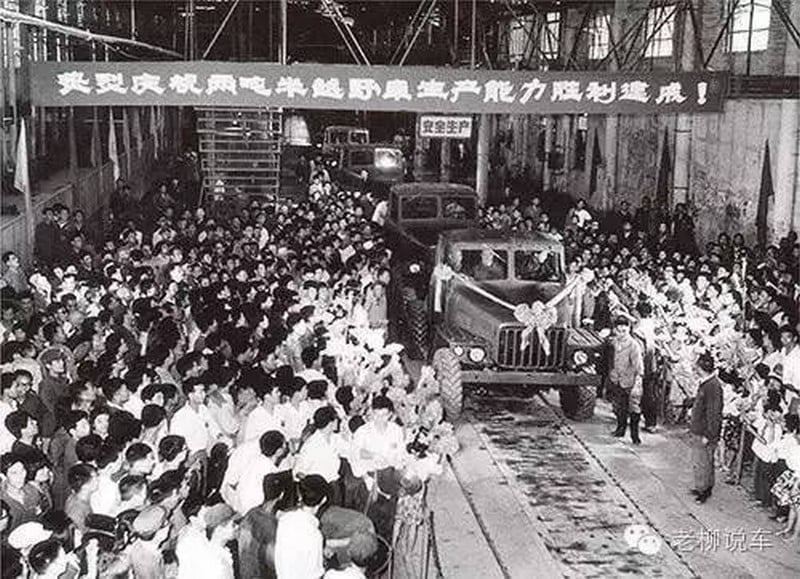

In June 1971 the first assembly line of SAW was finally ready and that was the end of the shed and the hand-built cars.

The military comes first

Due to the geo-political circumstances at the time it was clear that the first SAW truck would be a military vehicle. The design team took the well-established FAW Jiefang CA10 as starting point. They also imported American trucks from Dodge and International to benchmark their work against. The first design was a 2-ton truck, dubbed 20Y. The 20Y was developed in a matter of months and assembled in the shed. The army however requested an upgrade and so the truck evolved into the 25Y of 2,5-tons. This vehicle was built in small numbers before the factory was ready. A first batch of trucks was completed in the autumn of 1970.

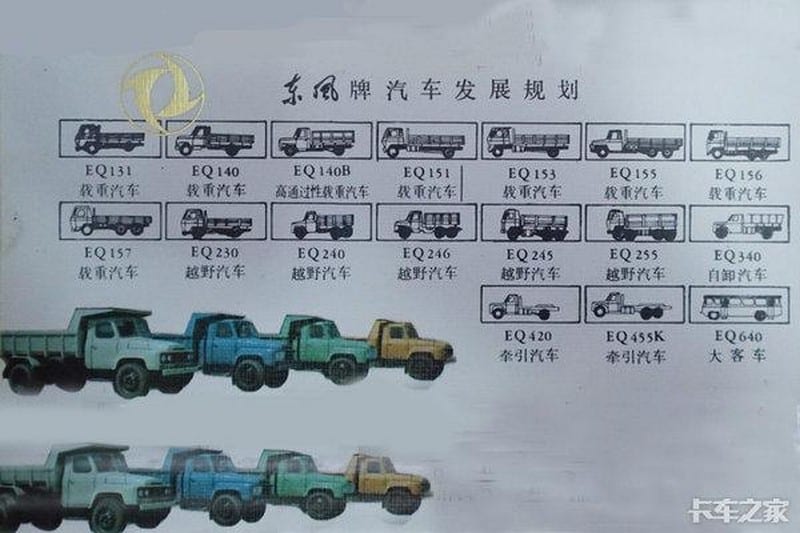

Regular production in the new factory commenced on July 1st, 1971. On the same date, SAW announced that the brand name of their product was Dongfeng. The military off-road truck in production was designated EQ240 and would be made in a variety of different specifications. All came with all-wheel drive and a self-built inline six cylinder engine (EQ6100). The EQ240 gained a sturdy reputation and saw action in many of the frequent border conflicts with neighbouring Vietnam.

SAW’s only client was the People’s Liberation Army. It meant a steady income, but also relatively low production numbers. And after the death of Chairman Mao in 1976 the internal unrest was quickly resolved and international relations started to normalise a little. So the demand for military products started to dwindle. All the while SAW had been increasing capacity, building a second assembly line and engaging a large number of small factories as part suppliers. The developments had a bad effect on SAW’s cash flow and it needed big brother FAW for a lifeline.

Civilian works

FAW had, with great success, produced the Jiefang CA10 truck since the 1950s. Commercial vehicles generally have longer life spans than passenger cars, but also trucks need to be renewed from time to time. So after two decades FAW had the successor to the CA10 ready, but instead the entire design and intellectual property was passed on to SAW. What should have been the Jiefang CA140 became the Dongfeng EQ140. Production of the truck started in 1978 on SAW’s second assembly line with a capacity of 5.000 vehicles per year. The EQ140 was the first Dongfeng to be sold to the general public, although it also appeared in many military versions.

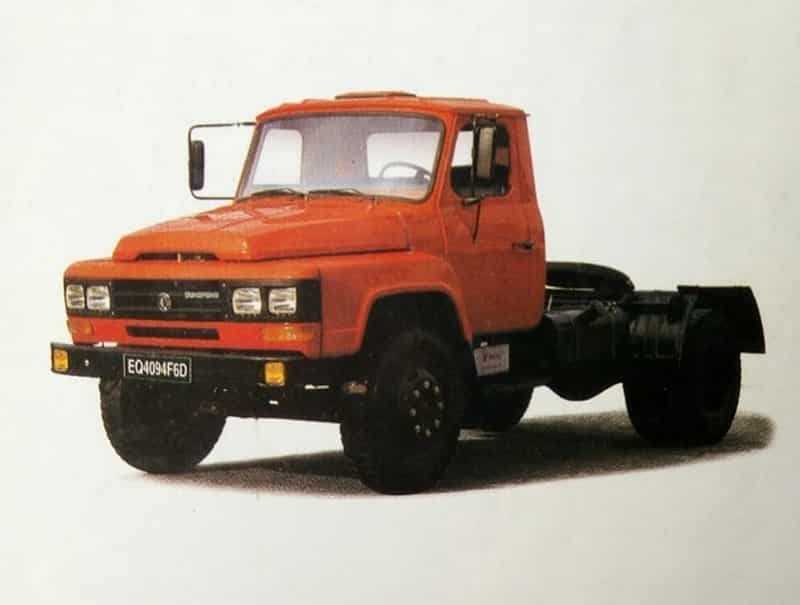

The 5-ton EQ140 became China’s quintessential medium-sized truck. The straightforward design with double round headlights on contrasting coloured background panel and the narrow grille is easily recognisable. Dongfeng made it one for every imaginable use case, dump trucks, tractors, refrigerated trucks, fire fighting vehicles, forestry and many more. It turned the company’s losses into healthy profits. Spanning a life of over three decades, the EQ140 remained in production until 2011.

Dongfeng wasn’t the only company manufacturing the EQ140. It followed the same principle as its competitors FAW and BAW, using a large network of smaller factories for parts manufacturing and assembly. Dongfeng supplied cabins and other components to several companies in this network, who assembled their own version of the truck.

Changing with the times

Until the 1970s, industries in China were under control of the government, either at federal level or lower administrative jurisdictions (provinces or cities). At the end of the seventies the government started supporting loose alliances between enterprises in the same industry. And in the eighties it finally became possible for one enterprise to own (part of) another. In 1991 the government laid out plans for consolidation and the formation of large-scale enterprise groups.

SAW obviously had to navigate within the existing laws and regulations and had the additional disadvantage of being in a remote area, with no supporting industries. So SAW formed a large network of related companies, over which it could have no control in principle. But smart lawyers always find a way. In the case of SAW, the company sold parts and components to its related parties 10% below market price. This allowed these companies to undertake semi-knockdown production. In return SAW would get 20% of the profits. However, they never collected the money and it was retained in those related companies. You could see it as a form of capital investment.

The next step came in 1981 when SAW created Dongfeng Automotive Industry Association (the company is also translated as Dongfeng United Automotive Industry Corporation or Dongfeng Motor Industry Joint Venture), let’s call it Dongfeng Industry for short. This new enterprise merged SAW with seven other business, namely Hangzhou Automobile Corporation, Hanyang Special Purpose Vehicle Works, and the Automobile Works of Guangzhou, Liuzhou, Chongqing, Guizhou, Yunnan and Urumqi. Dongfeng Industry initially owned 20% with the government retaining 80%, but the management control was turned over to SAW. Later SAW would obtain a majority interest in all these companies.

Dongfeng EQ140-I (1984)

Dongfeng EQ140-II (1994)

Dongfeng EQ140-III, built into the 2000s

One of the reasons for the establishment of Dongfeng Industry was to circumvent stringent limitations to production output, part of China’s planned economy. SAW and FAW, who set up a similar industry association, fought hard to get rid of these limitations set by a government committee called the China National Automobile Industry Corporation (CNAIC). In 1987 SAW gained equal managerial status to provincial governments and could now directly control other enterprises. In 1987 SAW held control over 200 smaller companies, two years later this had increased to 300 companies. In the end the government took away the control of CNAIC (and the limitations on production output) and enterprise groups like SAW gained far more independence.

The drastic economic changes of the eighties culminated into a temporary end point for SAW in 1992. On September 1st, Second Automobile Works changed its name to Dongfeng Motor Corporation (DFMC). It was a wholly state-owned holding company, directly controlling some 30 companies, including Dongfeng Industrial and a joint venture with Citroen (which will be discussed next week). On the same day Dongfeng Industrial changed its name to Dongfeng Motor Company (DFMG). This is the operational company responsible for making the Dongfeng trucks. It controls directly and indirectly the huge number of smaller companies, acquired in the past decade.

The Dongfeng naming confusion

In the coming weeks we learn about several of the Dongfeng companies and I promise to talk a bit more about actual cars. For now I must mention a well-known difficulty for anyone looking into the story of the Dongfeng empire: the company has given several of its business units very similar names, both in Chinese and English. So before we continu the story, I’ll give you quick overview of these names.

Dongfeng Motor Group Corporation Ltd. (DFMC)

(Chinese: 东风汽车集团有限公司 / Pinyin: dōngfēng qìchē jítuán youxiàn gōngsī).

The ultimate holding company, officially established in June 24, 1991. Until November 2017, it was known as Dongfeng Motor Corporation (东风汽车公司 / dōngfēng qìchē gōngsī).

Dongfeng Motor Group Co., Ltd. (DFMG)

(Chinese: 东风汽车集团股份有限公司 / Pinyin: dōngfēng qìchē jítuán gufèn youxiàn gōngsī).

Successor to the above mentioned Dongfeng Motor Company, officially established on May 18, 2001. DFMG is listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange.

Dongfeng Motor Co., Ltd. (DFL)

(Chinese: 东风汽车有限公司 / Pinyin: dōngfēng qìchē youxiàn gōngsī).

This is a Sino-Foreign JV between DFMG and Nissan (China) Investment, established on May 20, 2003. Also known as Dongfeng-Nissan. Several enterprises formerly directly controlled by DFMG, have been transferred to this joint venture. Prior to the joint venture, the name Dongfeng Motor Co was used for other enterprises within the group.

Dongfeng Automobile Co., Ltd. (DFAC)

(Chinese: 东风汽车股份有限公司 / Pinyin: dōngfēng qìchē gufèn youxiàn gōngsī).

Officially established on July 21, 1999 as listed subsidiary of Dongfeng Motor Group, but now part of DFL. DFAC is listed at the Shanghai stock exchange. The company produces light commercial vehicles.

Besides the similar company names, there’s also the brand name Aeolus, that can mean several things. After establishing Dongfeng Motor Corporation in 1992, the company management started to think about exporting its trucks. The name Dongfeng translates as ‘east wind’. In China the east wind is associated with a pleasantly cooling breeze during a hot summer day. Dongfeng’s managers however quickly discovered in many parts of the world east wind means “freezing your balls off in a harsh winter”. So in international communications they changed Dongfeng to Aeolus, the mythological Greek god of the wind.

This seems pretty straightforward, but the confusion starts in the mid-2000s, when Dongfeng launches its self-owned brand of passenger cars. In China the brand is called Fengshen, but in export markets Fengshen uses the name Aeolus. To make things even more complicated, since 2018 Fengshen cars in China carry the Aeolus name in western script on their trunk lid. So Aeolus either means Dongfeng or Fengshen, depending on context.

Next week

We will zigzag through the company’s developments by looking at one the Dongfeng Industry acquisitions (Liuzhou Automobile), the first passenger car joint venture (Shenlong Automobile with Citroen) and end with Dongfeng own car brands Fengshen (Aeolus) and Lantu (Voyah).