The Big Read: History of BYD

It was a sunny day when Wang Chuanfu parked his brand new Mercedes S-class in front of the entrance of his own automotive R&D center in Shanghai. Not much later, he had gathered a group of his most important engineers around the car. “Okay,” he said with a graceful gesture in the direction of the car, “Take it apart.” None of the engineers made any effort to step forward. “But it’s your car,” said one, and “It’s brand new,” added another.

The sun reflected in the glass façade of the building and made the Mercedes shine like a black pearl. Wang understood the stalemate he had created and grabbed the car keys from his pocket. In one smooth movement, he then carved a deep scratch from front to back in the paint of the Mercedes. “So, now there’s no more reason to keep it in one piece,” he said, leaving the keys on the hood of the car while he walked away.

Previous parts of Automaker Profile series

-

- Nio

- Changan

The right man…

Wang Chuanfu, born in 1965, is a remarkable man. His company BYD states that the acronym means “Build Your Dreams,” and they proudly write it out in full on most of their car models. However, in an interview long ago, Wang said that the letter combination had no specific meaning when he came up with it. Afterward, however, the interviewer states that a smiling Wang confided with him that the acronym really stands for “Bring Your Dollars.”

Wang ChuanfuWang has university degrees in chemistry and materials science and worked as a researcher and assistant professor at Beijing Technical University in the early 1990s. His area of specialization was accumulators and batteries, and because of that, he had a good overview of Chinese battery production. He saw opportunities to do things much better himself, found a money man in Lv Xiangyang, and went to Shenzhen to set up his own company. In February 1995, he registered BYD as a manufacturer of rechargeable batteries.

…the right place…

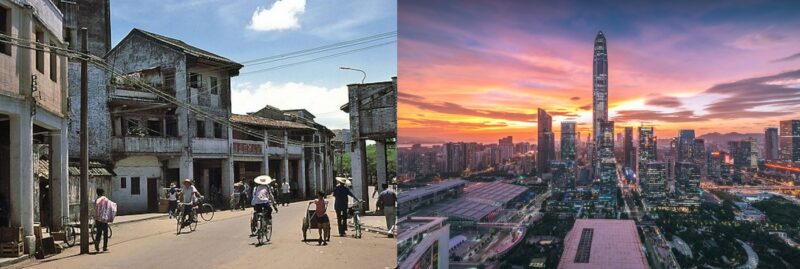

At the time, Shenzhen is a special place in China. In the mid-1970s, it was a swampy farming village of 30,000 population in the Pearl River delta, the river that flows into the sea just north of Hong Kong. However, in 1979 the central government selects Shenzhen as a special development area to experiment with capitalism. When Wang moves there, the city already has more than 10 million inhabitants. Today almost 15 million people live there, and together with eight surrounding cities, it forms the second largest urban agglomeration in China, with a population of close to 100 million people.

The Shenzhen experiment is a resounding success. The city is built on services, production, and lightning-fast innovation, and it is a good breeding ground for electronics. The city is called the Silicon Valley of China because, in addition to Wang’s BYD, companies like Huawei, Tencent, and DJI (drone maker) also originate from there.

BYD thrives in that vibrant environment. In addition to academic qualities, Wang also has a nose for good business. He starts making NiCd (nickel-cadmium) rechargeable batteries. To get to production, he uses a strategy that he will often repeat later, referred to in the opening paragraph: “reverse engineer”, “improve” and “make it yourself”.

Many Chinese companies have a dubious reputation when it comes to copying Western products. This is no different for BYD in its early days. Wang and his team take apart Sony or Sanyo batteries, analyze how they’re put together, and then make something similar under the BYD name. However, what makes Wang different from many Chinese competitors is that he does not stop at just a copy. He sees the importance of research and development from the start and spends a lot of money and time on it.

At that time, Shenzhen was flooded with people from the province looking for a job. Cheap labor is plentiful, and Wang takes advantage of it. Instead of buying expensive equipment to automate production, he hires thousands of workers and puts a lot of effort into optimizing the production process. With success, because when BYD goes on the Hong Kong stock exchange in 2002, it has become the largest producer of rechargeable batteries in China. In addition to NiCd, BYD also makes NiMH (nickel-metal-hydride) and Li-ion (especially LFP, lithium-iron-phosphate).

…the right opportunity

That IPO was initially a success, but in January 2003, the share price of BYD suddenly collapses like a plum pudding. Why? Well, Wang has bought a tiny car manufacturer in the northern province of Shaanxi. Wang was looking for areas to expand his business and had identified the auto industry as a prime candidate. He saw a huge growth market and a possible outlet for his batteries. Shareholders obviously disagreed with his views, especially because these ambitions had not been disclosed in the prospectus. But my dear, how wrong were those shareholders.

One of Wang’s hesitations about getting into the auto industry was it is very capital intensive and, therefore, hazardous nature of the business. In 2002, however, an opportunity arose. A large industrial conglomerate wanted to eliminate their ailing car factory, and local politics wanted to keep the factory going and employment secured. Wang could suddenly become a car manufacturer for a minimal price, and he also received a huge piece of land for free, plus some loans at a marginal interest rate. So, in January 2003, he bought Qinchuan Automobile.

That industrial conglomerate was China North Industry Corporation, better known by its trading name Norinco. Today Norinco is a huge complex of dozens of companies in the defense, chemical, and mechanical industries, but they have traditionally been arms and ammunition makers. When Deng Xiaopeng took power in China from Mao Zedong in the late 1970s, a long, turbulent period of violence came to an end. This meant a decline in demand for their products for the arms industry, and many of those companies sought other markets. Quite a number began to assemble vehicles.

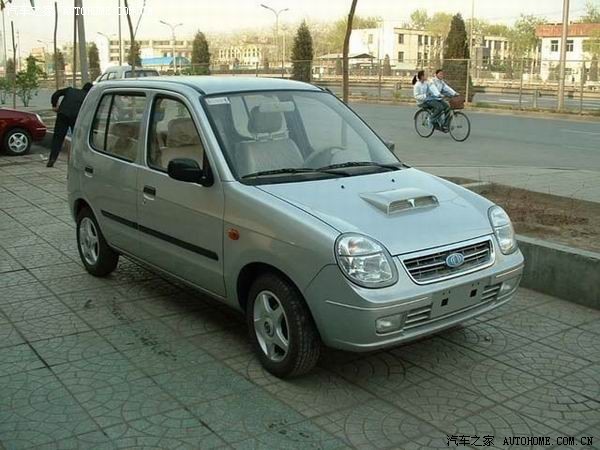

One of Norinco’s companies, Qinchuan Machinery Works (which made shells for bullets and missiles), also started experimenting with cars in one of their factories. Initially, they made a fiberglass car based on purchased parts, but in 1989 they signed an agreement with Suzuki. Like Chang’an, Jiangnan, and Jiangbei, they are allowed to manufacture Suzuki products under license. Qinchuan chooses the second generation Alto. The Qinchuan Alto is a considerable success, and the factory develops a sedan version of the car on its own.

At the end of the 1990s, the agreement expires, and Suzuki decides to continue with other partners. Qinchuan is developing its own car, the Flyer, which still relies heavily on the technology of the Alto. The company opens a new factory and in 2001 builds almost 20,000 Flyers. However, while sales are respectable, the company hardly makes any profit. At least far too little to sustain continuous growth, so Norinco hands over the car factory to BYD for next to nothing.

Building a dream

And so, we finally arrive at the opening scene of this article. In addition to Qinchuan Auto (which is renamed BYD Automobile), Wang also buys a factory in Beijing that makes molds and sets up an R&D department for cars in Shanghai. Wang storms the car market the same way he stormed the battery market. It starts with ‘reverse engineering’, a fancy word for copying but in BYD’s case, a little more than that. He has engineers take apart all kinds of cars, including his own S-class, to learn how to put them together and how to assemble the best. Then the mold maker in Beijing will supply all kinds of molds for parts at breakneck speed and enables BYD to build a parts industry and keep everything in-house.

A well-known complaint from early-stage suppliers: BYD orders a large badge of parts once or twice and never again. That’s right because then the engineers have studied the parts, a mold is made in Beijing, and the part is produced in a factory of BYD itself. A good example is the engines. The first BYDs are be equipped with Chinese-built Mitsubishi engines, but within a few years, the cars all are powered by BYD engines. These engines look suspiciously like Mitsubishi’s but are not identical. The engineers don’t just copy; they improve.

Initially, BYD continues to build the Flyer, but in 2005 their first self-developed model appears, the F3. This car sports an uncanny resemblance to a contemporary Toyota Corolla but costs a lot less. And that’s the niche BYD is entering: cheaper than the foreign models, but much better quality than all other Chinese competitors. The strategy works because production increased from 20,000 Flyers in 2003 to half a million cars in 2010. Just ask Elon Musk how difficult it is to achieve that. Incidentally, the growth stops there. In the ten years that follow, the annual sales of BYD always fluctuate around half a million passenger cars.

The rapid growth is because BYD has launched a complete range of cars in rapid succession from 2006 onwards. The first series of models almost all show similarities with the Toyotas of that time. BYD produces many variants and versions, specifically intended for a particular region or demographic group. All these models are equipped with petrol engines.

It was, of course, Wang’s goal to make electrified cars, and the first example followed in 2008. BYD presents the F3DM (dual motor), the world’s first plug-in hybrid. BYD’s first BEV, the e6, followed in 2010. This is an MPV, which is initially intended for the taxi industry (and even makes it to Europe in small quantities) but becomes available to consumers about a year later. BYD’s own growth is helped by government policies supporting the development of New Energy Vehicles, China’s name for plug-in hybrids and battery-electric cars. BYD happily collects the subsidies available for these low-emission or zero-emission cars. In 2019 BYD finally sells more NEVs than traditional gasoline models.

Diversification

Qinchuan was renamed BYD Automobile, but in 2006 BYD establishes a second automobile division, confusingly called BYD Automotive Industry. This branch actually houses all of BYD’s automotive activities, except BYD Automobile. And BYD no longer limits itself to passenger cars. Many readers outside China may have taken a ride in a BYD vehicle: the company’s electric shuttle buses and public transit buses are used in many airports and cities worldwide. And not only is BYD a major player in electric buses, but it also makes all kinds of electric trucks. From garbage trucks and distribution vehicles via specialized tractors for ports and airports to the huge 60-tonnes dump trucks used in mining. And for several years now, the company has also been making monorail trains, such as used on the public network in its home town Shenzhen.

BYD’s explosive growth is primarily a domestic affair at first, but it gains international exposure when Berkshire-Hathaway, Warren Buffett’s acclaimed investment fund, bought quite a few shares in 2008. About 10% of the company, to be exact. Partly because of this, BYD also gets on Daimler’s radar. Although the Germans already enjoy a long-lasting relationship with BAIC, in 2011, they also set up a joint venture with BYD. The first product of this joint venture is an electric MPV based on the B-class. The car is marketed under the newly created Denza brand. Mercedes, however, seems to lose interest in the endeavor rather quickly and concentrates its Chinese activities around Geely and Beijing Auto. Denza is now a somewhat forgotten brand, their only remaining model a rebadged BYD Tang.

A new dynasty emerges

BYD becomes a major player in the Chinese car market with its line-up of Toyota lookalike sedans but realizes it needs to move away from the copied designs. Its second-generation models, starting with the Qin in 2013, get a more distinct design. Chinese car manufacturers worked off and on with European design studios, but BYD is one of the first to employ a well-known designer as their design director. Wolfgang Egger, who built his career at Alfa Romeo and Seat, is hired in 2016. And so it happens that a little bit of BYD design gets transplanted onto other brands. The VW Group seems very fond of the reflecting panel between the taillights that BYD uses on many of its cars, and, oh the irony, the latest Toyota Corolla front end has quite a bit of ‘Dragon Face’ in it.

Starting with the Qin, BYD names all its second-generation models after former Chinese dynasties. The company also launches Tang, Yuan, and Song. The Tang is a large SUV, quite successful in the Chinese market, and as 550 hp plug-in hybrid could have been selling well in, for instance, the American market had it been available.

Over the years, BYD has transformed into a nimble or agile company. A small example showed at the beginning of the Covid pandemic. Several car manufacturers moved into making face masks or hand gels as car production came to a standstill. BYD produced face masks as well, but at the same time, they developed and manufactured face mask sewing machines. In late March 2020, they produced a hundred thousand face masks and several face mask machines per day.

The same agility shows in vehicle development. The Japanese brands lobbied for more lenient regulations for hybrids in the Chinese market, got their way, and the moment the new rules were adopted, BYD introduced its DM-I hybrid system with the world’s most efficient internal combustion engine. (To be fair, that title was taken from them by Great Wall Motors a few weeks later). And in the battery department, they responded to concerns about safety with the ‘Blade Battery’. These are long, thin, prismatic cells that can be assembled into a pack without modules. BYD was the first to pass China’s new ‘battery penetration test’ with flying colors. The cells use LFP-chemistry, so they are relatively cheap and less restricted by limited resources.

All BYD’s technology combined culminates in the Han, a large sedan that competes directly with Tesla’s Model 3. The Han is cheaper and well build and received mostly very positive reviews in the press. In one year on the market, it sold 100.000 times. Quite an achievement. The Han is BYD’s last second-generation car as the upcoming Dolphin is based on a new, more advanced, and flexible third-generation platform.

BYD’s strategy to make many parts in-house pays off handsomely in the current semi-conductor crisis. BYD is less affected than most because they make a good amount of their microchips themselves. To monetize its parts production, BYD has concentrated its component factories in a new subsidiary and called it Fudi. Direct competitors can purchase and use the parts while avoiding BYD branding. Fudi gained a successful listing on the Hong Kong stock exchange very recently.

The student and the master

In 2019 BYD and Toyota announced a joint venture that was established the next year. The new company is to produce Toyota BEV’s for the Chinese market. A remarkable development for two reasons. First, Toyota has been very reluctant to move into BEVs or PHEVs and concentrate its efforts on plugless hybrids. Second, some BYD managers have already suggested that BYD will develop the actual cars with BYD technology, and Toyota will be helping out with production technology and the shipment of logos. So BYD has come full circle. Once they made thinly disguised Toyota copies and from 2023 onwards, Chinese citizens will buy Toyota’s that are really BYDs in all but name. Now how is that for the student surpassing the master?

The Big Read: History of Changan